THE MOOR IS BURNING

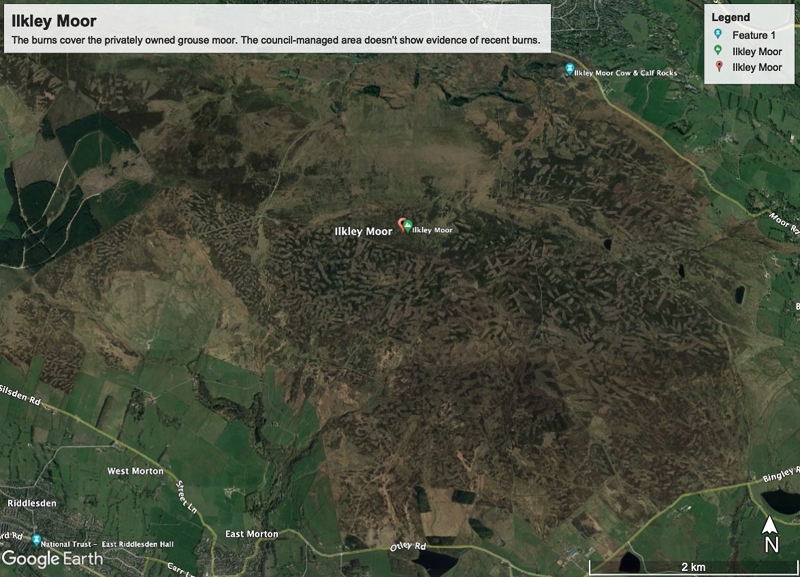

To the left of the wall: privately owned moorland showing burn scars. To the right: publicly owned moorland that has not been recently burnt.

Discovering scars

In April of 2022 I needed to do a research task for university.

I have to measure a stand of trees, so I take to Google Earth to identify a suitable location.

I figure that the moor is a likely place for an isolated stand, so I pinch the map over Ilkley Moor. I follow from the side facing the town to the side less visible and notice an odd pattern.

Most of the back of the moor is covered with marks like fat brush strokes from a limited pallet. Brown and beige and purple.

I zoom in and something tugs in my stomach. It would be cliché to say the hairs on the back of my neck stood up but true enough to say my chest seemed to pitch forward, a hole opening up where my love for this place sits. Up close, the marks aren't brushstrokes. They're scars and bruises.

Like raw, painful wounds the open sores cover the moor behind the ridge that blocks the view from weekenders.

The urge to stick my head in the sand washes over me. Pain here would be too close to home.

I started to wish I'd never opened Google Earth because I know what these scars are. They're burns.

The eco anxiety was overwhelming.

A short history of shooting

Before we go on, allow me to tell you a story about what happened to shooting for sport in our country. It's easy to malign the sport but we have it to thank for the preservation of the likes of the New Forest and the Forest of Dean, previously royal hunting grounds.

Shooting used to be a very skilled sport. Think of people painstakingly tracking deer for hours, only to miss the shot because of a change in wind, or groups walking or riding through woodland or bush, using tracking skills to find the animals and waiting patiently for an opportunity to shoot.

You had to be a good tracker, good at hiding, and a good shot - often through trees or from distance. There were natural densities of quarry, surviving wild on the food available in the landscape and they weren't always easy to find.

This is how shooting was in the eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Limitations of guns at the time kept it this way. Shooting grouse was about a long walk across the moor with a friend, occasionally shooting at a bird flushed by your footsteps and then walking again whilst the guns were reloaded.

From the 1850s things started to change. Improved rail links and guns that were easier to reload brought rich people from the south to Scotland and the north of England. These men (they were almost exclusively men) wanted to partake in shooting as a status symbol, a backdoor to the upper class (or at least a way to pretend you were part of the landed gentry).

A new era of shooting was born. To pander to men who didn't have the skill to shoot and didn't care to learn it, driven grouse shooting industrialised.

Sheds or small enclosures (aptly called 'butts') were erected across the moor for men to shoot from. To make shooting easier, the moors were artificially stocked with grouse. The need for more grouse drove management of the moor to produce as many grouse (and as little of every other species) as possible. The moor was covered with food and medicine for the birds. Predators such as birds of prey were persecuted and moorland was drained and burnt to encourage new growth of ling heather, the type that grouse like to eat.

Burnt moorland, with a stone butt at the top of the frame

It's a pattern repeated across the shooting industry. Artificial densities of deer are kept on uplands and millions of non-native pheasants are reared in captivity and released to be shot every year.

These days, shooting grouse is more like shooting fish in a barrel than it used to be. The men (it's still mostly men) ditch their city suits to sit in a butt in quilted coats and flat caps and shoot at hundreds of birds raised from the heather directly in front of their window. They kill almost half a million grouse a year.

Moorland burned by land owners for grouse shooting

The moor is burning

It was October before I revisiting the scarring of the moor.

Keen to practice my newly learnt map reading skills and searching for ancient burial sites I set off to the highest point of the moor. When I reach the trig point, I continue along a stone path over the wet ground parallel to a drystone wall topped with barbed wire.

As we crest a hill, we notice smoke on the other side of the wall. I feel cold recognition slip down my back as I raise my binoculars and see the moor burning. On our side of the wall, the moor is boggy, purple and orange heather surrounded by puddles of dark mud and peat. On the other side of the wall the moor is drier and the vegetation darker.

I can see the scars. There are patches with white, dead heather. Newly burnt patches are black, charred plants blowing away in the wind, dry ground cracking.

In the distance, smoke rises from the ground. Peat that has been soft and damp for millions of years feels the heat of fire. Carbon that hasn't seen sunshine since it was in the bodies of ancient species is released into the air.

Burn scars on Rombalds Moor

What the burning means

For a while we were okay with the burning of moorland because it saved much of our uplands from falling into the grips of the forestry industry and being taken over by non-native conifer plantations (although you can see small plantations on most moors).

Today we recognise it as a serious problem. Much of the moor is peatland. Peat is a special type of soil that takes a very long time to form and is composed of decayed organic matter. It's mostly found in upland boggy areas and supports globally rare ecosystems. Our peatland also holds a huge amount of carbon: more than the forests of the UK, France and Germany combined.

Our peatlands should be a huge carbon sink, dwarfing the carbon sequestered by our trees. Instead, they're a source of carbon emissions, and 75% of those emissions are a direct result of burning.

Burning not only releases carbon, it also damages the ecosystem, pollutes the water, and reduces the ability of the ground to absorb water, increasing the risk of flooding.

The burning on our moors - carried out under the direction of private landowners - has been increasing steeply. It increased 11% per year between 2001 and 2011.

A half-hearted ban (only on deep peat) was introduced in 2021, but despite its limited application is still routinely breached. An investigation by Greenpeace's Unearthed shows burning without a licence in areas of deep peat, and according to data from Natural England the area I saw burning on Rombalds Moor has deep peaty soils.

A patch of burnt heather, with a line of wooden butts

A class issue

Mark Avery explains in Inglorious why the controversy over driven grouse shooting and the burning of our moorland is a class issue.

Our moorland is owned by the super-rich. Ownership is concentrated in the hands of the few, and the cost of shoots means that those who benefit from grouse shooting are firmly in the 1%.

Avery explains that the vast majority of the British public do not benefit in any way from grouse shooting. They have no access to the land and the industry creates few jobs. The private landowners release huge amounts of carbon to the detriment of us all in order to make shooting easier.

Shooting isn't the problem; fragile masculinity is

It's worth noting that shooting grouse isn't the issue here. There are other debates to be had about shooting, but the problem for our moors is firmly grounded in industrialised driven grouse shooting.

Managing the grouse shooting industry so that the experience edges further towards shooting fish in a barrel is what's causing the problems. If there wasn't the pressure to generate huge artificial populations of grouse in order to make shooting them quicker and easier there'd be no need to engage in most of the harmful behaviour associated with grouse moors.

The management of moorland is controversial due, in no small part, to the fact that moorland is a human-created environment. Human clearances of woodland created the landscape we associate with our uplands, so it's difficult to pick a baseline and opinions differ about the best management techniques. The part of this moor that isn't burned has a lot of bracken, which some conversationists hate. The answer isn't burning the peat and persecuting birds of prey, but that isn't to say it's easy to gain consensus on the way forward.

If shooting grouse returned to being a sport that involved long walks on the moor, guns that are slow to re-load, small 'bags' (numbers of birds killed) and, importantly for the integrity of the sport itself, required more skill, patience and practice, our moors would be a better place, we'd release less carbon, our ecosystems would suffer less harm, there'd be less frequent and less severe flooding, and our wonderful boggy uplands could fulfil their role as our greatest carbon sink.

Burnt heather

Share with your friends

Subscribe to learn more

Join me in exploring our natural world and cultural heritage as we learn how to protect and restore it. Get notified on my latest posts and a monthly newsletter on wider conversation topics for us to chat about.

Recent Posts

If you enjoyed this one, then you might like these too.